It’s been known for nearly a decade that the oral bacterium, Fusobacterium nucleatum (Fn), is found enriched in Colorectal Cancer (CRC) Tumors. Higher abundance of Fn in CRC tumors is associated with recurrence, metastases, and poorer patient prognosis. So should this bacterium be eliminated from the mouth at all costs? The answer is likely no - and new research can help answer why.

For background, Fn is one of the most abundant species in the oral microbiome - found in nearly everyone’s mouth (95% of all Bristle users’ oral microbiomes have Fn). Fn can be a confusing character, as it is a normal inhabitant of healthy mouths, but is also commonly associated with gum disease, as well as a number of systemic health conditions - how is this possible?

The answer may come down to genetics - not yours, but the microbe’s! Research has identified that Fn actually has 5 unique “subtypes,” or strains based on genetic differences. Similar to how Covid-19’s strains like Alpha, Delta, Omicron, had varying levels of contagion and severity of symptoms - Fn’s subtypes also have key differences in how they affect our health. We are still at the forefront of research on these subtypes, but new research may have uncovered that one Fn subtype is uniquely responsible for its impact on CRC.

Zepeda-Rivera et al from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center published new findings last week in which they propose a subtype of Fn, Fn animalis, may be the culprit behind Fn’s relationship with CRC - or more precisely, a “clade” (variant) of Fn animalis may be.

Confusing? We’ll explain.

Finding C2

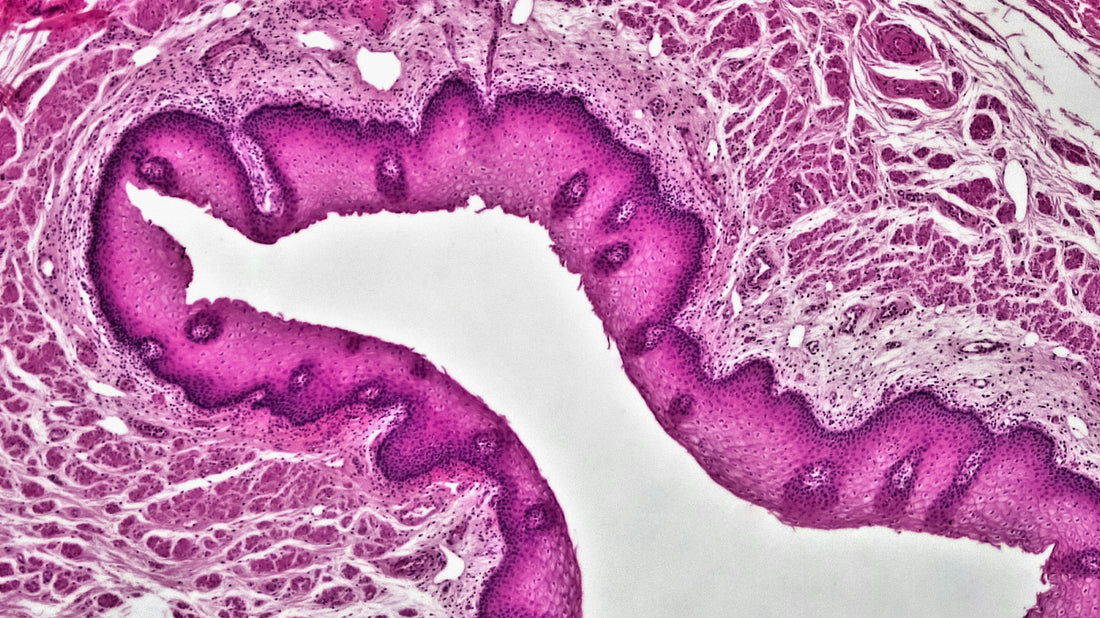

In the study, the researchers performed deep genetic analysis of Fn samples taken from CRC tumors and compared them with Fn samples from healthy oral microbiomes. In doing so, they uncovered that there were two distinct clades (variants) of Fn animalis, FnaC1 and FnaC2, and that FnaC2 might have genetic features making it uniquely suited for colonizing CRC tumors.

Looking for C2 in Databases

To test their hypothesis, they first checked the available tumor and oral microbiome databases of patients with CRC. They found that both C1 and C2 were present in saliva, but that C2 was significantly enriched in tumor samples.

Animal study

Next, they ran a study in *mice to see how adding C1, C2, and a control would impact their rates of developing intestinal tumors. After introducing the Fn subtypes orally, they saw a significant increase in the number of intestinal adenomas (tumors) in Fna C2-treated mice compared to both Fna C1 and vehicle control independently.

- Note: these mice were given molecules to induce colitis (gut inflammation) making them especially susceptible to infection and tumors.

Human study

Lastly, they used genetic analysis to characterize the Fn from tumors of 116 patients with CRC and from 62 healthy patient tissues. They found that C2 was significantly enriched in tumor tissue, with C1 and other Fn subtypes not being significantly enriched.

So how common is Fusobacterium nucleatum animalis C2 in patients with CRC?

To answer this question, they analyzed stool samples from 627 patients with CRC and 619 healthy patients. Fna was detected in 29.2% of CRC patients and 4.8% of healthy patients.

So what does this mean for you?

This research may be very exciting in the management of CRC, as it offers a new culprit that drugs and therapies can target in hopes of mitigating CRC progression. But we still have much to learn about its significance to our oral and overall health - and it’s important to recognize that.

There has already been a surge of press and social media posts warning that if you have Fn you may be at risk, and advertising ways to eliminate it to keep you safe. As we’ve discussed here, this paper suggests most Fn subtypes are not associated with CRC, and other research suggests some Fn subtypes may be critical to a healthy oral microbiome.

What can you do to prevent Fusobacterium nucleatum animalis C2?

In the paper, the researchers discuss that Fn may travel through the body and reach the colon through either:

- Navigating through the digestive tract from being swallowed

- Entering the bloodstream through cuts in our gums and mouth

Normally, our stomach acid will kill oral bacteria that we swallow, but in cases of chronic gut inflammation (such as IBD), our guts are more susceptible to colonization from oral bacteria. You can learn more about this relationship in our research article, "The Oral-Gut Axis".

Healthy gums do not bleed. By practicing proper oral hygiene (including flossing), and incorporating a healthy diet, habits, supplements, and/or oral probiotics - we can keep our oral microbiomes balanced and reduce our risk of inflammation which can lead to gum disease and bleeding gums.

This underscores the importance of maintaining a healthy digestive system, both in the mouth and the gut, which starts in large part with a healthy oral and gut microbiome.

At Bristle, we are doing research of our own to help give you the tools to measure, understand, and balance your oral microbiome - and will share more findings from ourselves and the community as we discover them.

As always, please feel free to contact us with any questions!